What you need to do to take your agents from demo to runtime

Most teams still ship (or try to) AI agents the way we used to ship a script:

Someone defines a task → wires a model → adds a couple of tools → runs "hello world" → ships.

That's fine for demos.

It's not fine when the agent talks to production systems, customer data, money - and especially not when it runs alongside many other agents, at scale.

So we drilled into this with different teams (different sizes, industries, levels of agent maturity) and tried to answer one question:

What does a Secure Agent Lifecycle actually look like?

Meaning: how do we treat agents like first-class workloads that can be continuously deployed at scale, observed, baselined, enforced, and re-approved when they change, and how is that different from the traditional SDLC?

Out of that work, two missing building blocks kept showing up:

- The Behavioral Rail

- The Runtime Re-Approval Gate

The rest of this article is about those two.

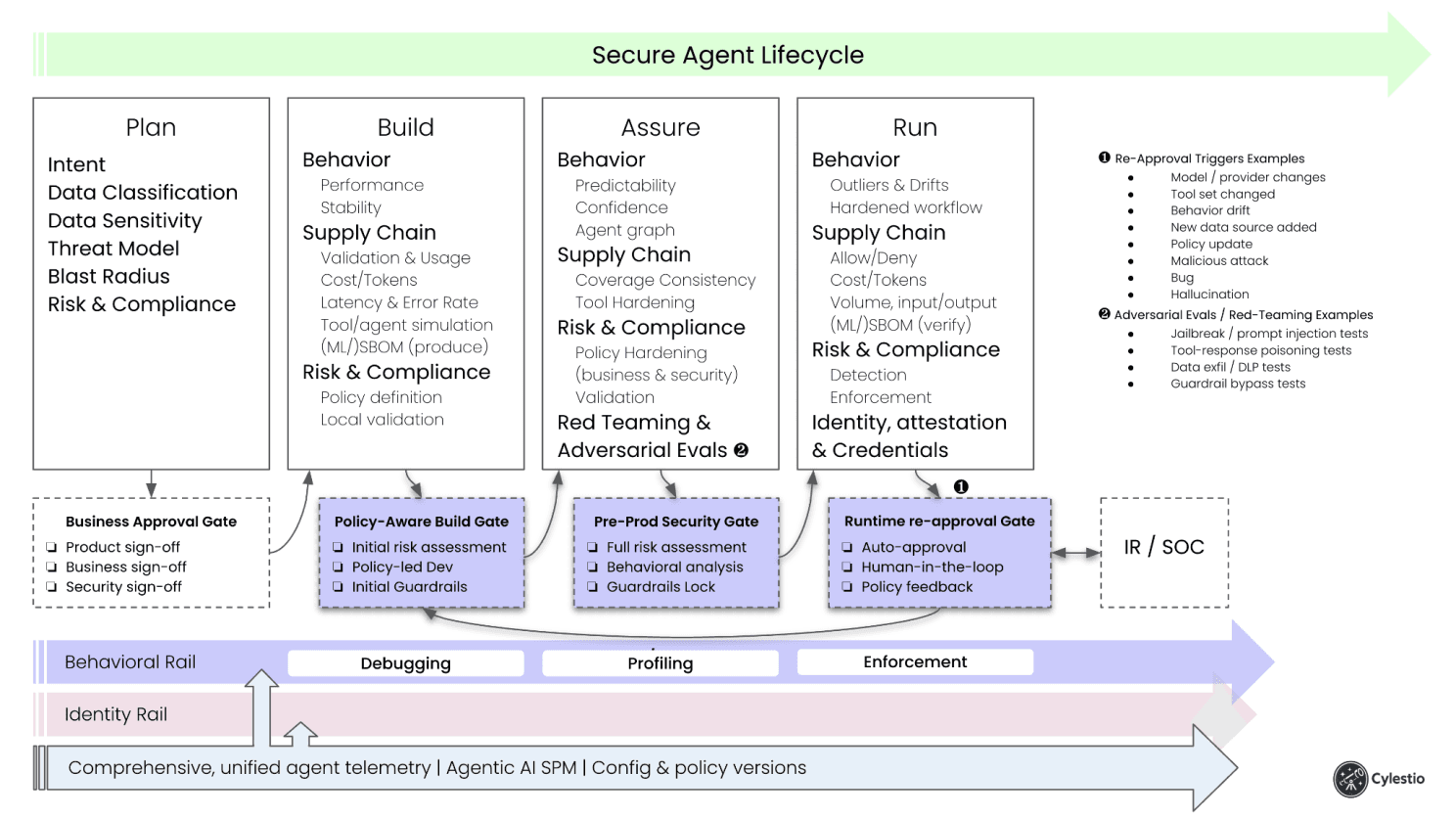

The Secure Agent Lifecycle (high level)

You can think about it like this:

Plan & design the agent

Define business goals, product constraints, security requirements, data sensitivity, and blast radius. Make sure the relevant teams actually sign off.

Build the agent (policy-aware)

- Policy-aware / policy-led development - know what is allowed/blocked while you're writing the prompts and code (in a world where AI is writing a lot of it, this is power back to the developer).

- Initial risk assessment - shift agent security left and detect obvious risks during development.

- Initial guardrails - org-wide requirements or product-specific rules, the initial boundaries that makes us feel safe enough for deployment (but not the refined that we'll learn after deployment).

- Behavior stability - is this really one agent, or did we just create 20 workflows inside one entity? If it's the latter, split it into smaller agents with clearer goals.

Assure the agent

For agents, static tests are not enough. Even our current CI/CD "dynamic environments" are not enough. We need:

- Evaluation stages

- Red-teaming and adversarial evals

- Behavioral profiling - baselining how the agent actually behaves and how predictable it is.

The pre-production/security gate should look at all of that. The behavioral profile should influence all the other metrics. This is also the stage where we harden the agent workflow, tool execution and policies based on actual behavior (and see how much of that behavior we even covered in tests).

Run the agent

Once it's live, we need to enforce policies and expected behavior. That's not just "hard-coded rules." A lot of rules need to be dynamic and adapt to the actual scenario and inputs/outputs the agent is seeing. We need to detect behavioral drifts and outliers, and then decide, is this:

- A legitimate evolution?

- A bug/hallucination?

- A malicious attack?

And based on that: auto-approve, trigger human-in-the-loop (and which human? dev / sec / ops?), or block.

This last part, deciding what to do with runtime changes, is exactly where the second building block comes in.

The Behavioral Rail

When people say "observability for agents," they usually mean: I can see the prompt and the tool calls.

Nice, but not enough.

Agents are probabilistic and context-sensitive. We will never test every possible path or every tool-input combination (and that's okay). What we need is a way to see what actually happened in the real environment and react fast.

That's why we make behavior its own lane:

1. Behavioral Debugging

Early on we just watch: what tools does the agent actually call? what inputs make it weird? where does latency spike? This stage is noisy and developer-friendly.

2. Behavioral Profiling

This is the important part: profiling is not "we tested everything." Profiling is "we learned what this agent actually does in our environment." Which tools it tends to call, which data it touches, what it sends out, how much it costs, what systems it impacts. So when something unexpected happens, a new tool, a new destination, a bigger blast than planned, we know about it right away and can assess: is this legit evolution, or is it wrong/dangerous?

3. Policy-backed Behavioral Enforcement

Only after we know "normal" do we enforce "allowed." Now we can allow/deny specific tools, block data exfil, require a human for high-risk actions, and alert on drift.

The point is: it's acceptable to release an agent that hasn't been fully evaluated, as long as you have profiling and runtime visibility to catch unexpected outcomes and impacts quickly.

If you observe → profile → enforce, you get both speed (ship earlier) and safety (react when reality diverges).

The Runtime Re-Approval Gate

Traditional SDLC assumes change is explicit:

- someone changes code

- pipeline runs

- we approve

- we deploy

AI agents don't always change explicitly.

- the model was updated by the provider

- a new MCP/tool was added

- the prompt was tuned

- the data source moved

- cost or tool volume drifted

- a new policy pack was deployed

In classic SDLC, most of these are change-management events.

In AI, they sometimes just… happen.

So we add a Runtime Re-Approval Gate - a standing checkpoint in production that asks:

"Has this agent drifted far enough from its approved behavioral profile or supply-chain definition that it needs to be re-approved?"

How it works:

- we feed runtime signals (drift, new tool, new model, DLP hit, policy update, suspicious behavior, …) into the gate

- if risk ≤ threshold → auto-approval, keep running

- if risk > threshold → pause/limit/alert → send to the owning team or SOC/IR → re-approve

This is the missing loop.

Most teams can define policies; far fewer can pull an agent back into governance when reality changes. The re-approval gate is what closes the loop.

Why this is different from traditional SDLC (and still compatible)

We're not trying to duplicate every step from AppSec / DevSecOps.

We're adding the things AI agents actually need:

- behavior as a first-class concept (observe → baseline → enforce)

- runtime re-approval when models/tools/policies/data change

- agent supply chain (SBOM / ML-SBOM) both produce and verify

- adversarial / LLM-specific assurance in CI/CD

- unified telemetry powering all of it (prompts, tool calls, model version, policy decisions, config versions)

Everything else - plan, build, assure, run - is familiar to security, platform, and DevSecOps teams. That's intentional. We're extending the SDLC to handle autonomous, evolving software - not replacing it.

Originally published on LinkedIn

View original article